| che-chin |

|

|

|

Name:

Che-chin Indigenous:

Galen, Sargasso seas. Use:

No modern uses. Habit:

The plant forms loosely linked mats on the sea’s surface, individual

plants live for a few years. Rarely the plants form mats off the coast,

though most vegetation trapped on the land does not survive desiccation

between high tides. Marginal aquatic forms of Che-chin do exist, though

they have lost their ocean going habits. Favoured

conditions: Che-chin is one

of the more common plants found in Gadarren’s floating vegetation, it

is predominantly found in the temperate seas in the shallow water off

the continents. Many of the larger mats of vegetation continuously

re-circulate in the currents, though occasionally the mats come closer

to shore, or even fragment and become stranded. Che-chin is a hardy

marine species, though can not tolerate conditions any significant

degree below freezing, it also benefits from unobstructed sunlight, not

generally a problem unless it is growing within an already complex

Sargasso. Structure:

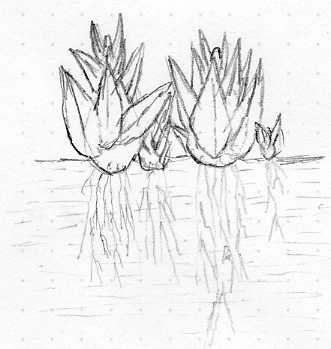

The plant is simple in structure; leaves are arranged in a rosette

around a single bud. This bud forms the bulbous float that supports the

plant in the water, though the upper most growing tip of the plant is

dense growing plant tissue immediately beneath this the tissue is

expanded and pithy. This swollen bud/stem provides the buoyancy of the

plant. The inner foamy pith plays little other part in the plants

biology, the real living tissue is the skin surrounding the float, the

leaves connect to this skin by simple axils, sometimes at these leaf

axils smaller plants develop which is the principle route through

vegetative propagation occurs. The plant grows to about 20cm across,

tapering slightly to a conical shape. Viewed from above the leaves are

delicately arranged in a single spiral, with both the angular spacing

and the leaf size decreasing as the leaves approach the central growing

tip at the top of the cone. From the spheroid bottom of the plant a

number of major roots grow from the bottom a little like tap roots,

elsewhere on the plants underside finer and mat-forming horizontal roots

grow. Though both root types are important for the plant to exchange

minerals and water with the sea, the vertical roots are specifically

important because these long roots intersect the subsurface currents are

in part responsible for defining how the plants move. Foliage:

Che-chin’s lineage is from a relatively separate group of plants in

Gadarren’s ecology, the leaves are simple, they do not show any

ribbing or complex vein structure. The leaves are almost uniformly

thick, and lanceolate. The leaf junction with the body of the plant is

simple, though as mentioned above this axil can develop new buds that

expand into new plants. The leaves are green/bronze though the bronze

colour can reflect a defence response to excess sunlight, or other

stress (e.g. UV). Sometimes a reddish/bronze vertical stripe can be

observed from the leaf tip to the leaf axil, though certain species

exhibit this more frequently than others, the reason is not genetic, but

rather a combination of epigenetic and environmental factors. Flowering

and fruits: Vegetative propagation in the most significant route for

reproduction in most species, and this occurs as a simple budding

process, where the new plantlets abscise off the parent. Rarely, and

seasonally the plant does produce flowers. The sexual parts of the plant

develop as a ring beneath the growing tip, and are simple in structure.

The male gametes are formed in papules growing in the skin and are

released either through contact (for example by striking with another

plant), or through desiccation and splitting of the skin by a

combination of aging and heat. The female gametes are also on the skins

surface though supporting cells that excrete a droplet of dew over the

ovum. Fertilization is usually through contact with a neighbouring

plant, where the male pollen is trapped on the dew like beads on the

opposing plant. The fertilised egg is briefly retained until it grows to

form a spore, which is then shed from the plant; from this point the new

embryo is independent of the parent, though marine fauna frequently

consume the young seedlings. Sexual reproduction is more successful in

established Sargassos as the other plants hide and nurture the

developing plants. In terms of reproductive routes sexual reproduction

is favoured when the plants are mat forming, where not only the mating

partners are available, but also an increased chance of progeny

survival. Sexual breeding is also an important way of exchanging genetic

material in communities as well as developing favourable characteristics

(genetic variety). Asexual reproduction by contrast is best suited for

isolated plants, where it is energetically favourable and more

successful, also by this route individual plants can give rise to mats

where as seedlings are frequently lost to the open sea. Cultivation:

Che-chin has essentially remained a wild plant and has not been widely

cultivated. |